The news is snapping up our attention

but the facts are lost in the noise.

The speakers and tweeters grab our cheeks

and turn our faces to their most

blatant lies and horrific facts so hard

that we fail to notice the grays on the edges,

and we see only sharp edges

of discord, blog-soldiers at attention

ready to come down hard

numbing us with more noise.

What we might fear most

is a mere slap on the cheek

or even a kiss on the cheek

because we are the ones gone soft at the edges.

We put on our most

determined look and feign attention

and add our clicks to the noise

because our lives are hard.

We pound our keyboards hard

but from real action we turn our cheeks.

On the streets we block the noise,

don headphones and skulk on the edges

trying not to draw attention.

We ignore those we should hold most

though what we hope for most,

the thing that is really hard,

is that our children need attention.

The tears run down their cheeks

and wet the soft edges

of their mouths which make no noise.

We must make some noise.

There are so many of us almost

forced to the very edge.

The fears will push back hard

but we won’t turn our cheeks.

We control our attentions

and we’ll make some noise about what’s hard.

The most meek among us will show their cheek.

Those on the edges will have our attention.

It entered as soon as I opened the screen door

and fluttered in behind my bed

and rested on the wall there

more restful than I. It was

a small white visitor to our family cottage

with a head shaped like a Robin Hood cap.

The next night it was there

on the ceiling, turning brown.

It was the spirit of my mother

watching while my daughter

tried the old face powders

still in the drawer

still smelling sweet

and none of us willing to toss them.

Celia tipped one cheekbone to the mirror

then the other, the way her grandmother would

when putting on my face for cocktails

or checking her hat for the symphony.

Later, the moth watched from the bureau

where I’d sniffed from my grandmother’s

glass perfume bottles long ago.

The next night the moth joined us

for bedtime reading in the children’s room.

Last night it was by the sink when

I went to brush my teeth for bed.

It was a giant among the multitudes

of lesser moths gathered by the nightlight.

The jutting head, like one of Mom’s crazy hats,

and large dark eyes worried me a little

though it was now very still,

its wings turning to powder.

Looking down from the high library windows

I watch the pigeons do their funky flap-flap-

flapping before they turn to glide in the air.

I finally feel the feeling I’ve missed

slogging at the base of the high-rise canyons,

dodging slush splatters from cabs whose

bright yellow looks like a warning.

I’m writing in a dreamlike trance

trying to enter the surrealist perspective.

I write about flying for the handsome Italian

professor of Literature and Political Ideologies.

This time I’m sure I’ve got something.

So I sit upright, later, in his office

and he rains down his approval.

Hands fluttering in gestures of generous favor,

he flips through the pages marked in red, Yes!

and finds the passage he’s sliced

into line segments and reads eagerly,

declaring, It’s a poem! and then I began.

She spends long hours in the squalor

of her room alone, surrounded by

inside-out clothing, open drawers,

half-burnt candles, books,

papers, paints and pencils

layered in snacks and dishes.

She’s trying on a her to find

the one she can live with, the

one that makes sense with her

lovely face, lithe figure and

the world seeming all wrong

with posturing politicians and

hungry bosses. Should she hide

in lumberjack shirts and thick boots,

or change it up with bleached hair

and jewelry? Wear something

tight-fitting, or sack-like?

She whisks by me, striding in her

styles, grabbing food to go,

taking my car, making me remember

all the versions I had tried

and kept or cast aside.

Before we close the lid on our treasure chest of last summer’s pleasures, here’s a peek at one of mine: a reading by Mary Oliver on the lawn at Longfellow House in Cambridge, August 17. Organized by friends of Longfellow House, The Parks Department, and The New England Poetry Club, this event drew several hundred attendees. I glimpsed several Ibbetson Street friends and associates there, and no wonder. Diane der Hovanessian, President of the New England Poetry Club, conveyed to Oliver in her introduction there the May Sarton Award for a poet who inspires poets.

Despite the sometimes cool emotional quality of Oliver’s work, her reading persona is comfortable and friendly. She interjected a fair amount of commentary between poems, and even outlined her reading strategy as an opener: She would read a few from her new book Owls And Other Fantasies, a few new poems, and a few poems in progress. “I should have made a list of rain poems, “she remarked in acknowledgement of the drizzle. Oliver is a devout naturalist, which may explain why she was completely undaunted by the weather.

She opened with an enormously popular poem—Wild Geese, which ends

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting–

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

After which followed a great round of applause with a quick hushing in anticipation of the next gem. In that moment, a songbird from the bushes just behind the audience broke into a melodious offering of its own, causing us to laugh at its impeccable timing. Oliver’s comment that “There’s a blessing” echoed our feeling for her.

Oliver’s quiet enthusiasm bubbled over the bouquet of umbrellas from The Nature Conservancy, Harvard and other schools and art museums in the audience. Whenever she read a new poem she remarked that those were particularly fun for her to read. When she read I Found a Dead Fox, she said she thought that might be her favorite; but when she read Yes,No, she said that one was definitely her favorite. That poem reiterates a common theme in Oliver’s poetry, that “to pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.” I did my best.

I had heard Oliver read many years before at M.I.T.’s Poetry at the Media Lab series. There she told of her strategy of keeping lines short in order to compel new readers not to be intimidated by poetic form. Here again she mentioned she hoped to get the “unconverted to stick with it” by doing without punctuation as much as possible. “If you don’t see a period, you keep on going,“ she said. She also mentioned that she likes to use a lot of questions in her poetry. Whatever she does to pique our interest seems to stem naturally (not affectedly) from the delicious generosity of her poetry.

One of the final poems Oliver read proved to be my favorite—The Summer Day, and I can’t think of anything better that I could have done with my summer day than to hear her read at Longfellow House. She was unable to stay for book signings, which was a shame. But to be honest I wanted to scurry off myself because I was getting a bit damp, though still smiling.

And did you feel it, in your heart, how it pertained to everything?

And have you too finally figured out what beauty is for?

And have you changed your life?

From The Swan, by Mary Oliver

Cheers, Linda Haviland Conte

It is considered unlucky

in Chinese wisdom to

declare your child beautiful.

And how could a thing of beauty

have sprung from the brambles

of our unkempt garden?

My little weed sprouted early

and was slow to sink his roots

and reach his tendrils up

around the chain link fence.

No demon dragon should note

the very delicate touch

that aches his mother’s heart.

We gently bathe him and

train his leaves toward the sun.

He has already greened a deep

corner of our lives. But to you,

evil spirit, he is nothing. Pass by!

It starts out so quietly,

just a guy wandering around his house

and yard on a rainy spring day.

It’s not even a poem really.

But when it’s all over,

you may find yourself

mourning the loss of your father,

even weeping at the window.

The poem I thought I would write today,

full of spiky wit

and swipes at self-annihilation

melts into the fog of my own

mysterious gray day.

[see Where I Live, p. 130, from Sailing Alone Around the Room by Billy Collins]

Michael came out half-baked

and finished up in the incubator.

It took him a week to learn to suckle.

We spent hours each day in the NICU

kangaroo-ing him next to our skin

and learning CPR before we took him home.

I worried so much over everything I did for him.

At six weeks I worried he’d not yet smiled,

then realized he had no role model for smiling.

The nurse was frantically calling for a doctor

when Celia was born,

but she managed to break out on her own.

As she was being cleaned up across the room,

I summoned myself to address her:

Hi, Sweetie. I’m right here.

She turned her head straight to me,

strong-willed and ready. Lucky girl,

she basks in the love first forged by her brother.

After we’ve molded them and had

their edges smoothed by school and sports

we let our son and daughter go

to be fired by the world of work.

We peek at them through a tiny kiln door

and pray the heat is right—that they

will harden and not crack,

that love and experience will glaze

them gloriously, while we rest

well-used and chipped in our cupboard.

Sometimes something precious lies

quite close to you, but you don’t see it,

or don’t know its value, or know you want it.

Someone leaves it for you, or brings it

as a gift, some friend, some god.

My prayer for you is this: that

you will be a gatherer in times of abundance,

that you will be ascetic in times of scarcity,

that you will find joy in much and little,

and always be in harmony with what is.

Pump thrumming in the skiff house,

inflating the enormous tube

for kids to ride on behind a motor boat,

squealing with pleasure, teens

inventing tricks to tease grownups

and little ones. Come swim with us!

What’s for dinner?

Birds chortle. Sun burns.

Sweet grasses perfume the air.

If I could have this much beauty

and this old rocking chair

every day with good health

and the accompaniment of birdsong,

the sounds of purposeful movements

stirring in the cottage, mesmerizing

sun flecking off the waves and wakes…

If I could have just a few hours

maybe weeks, maybe then my

soul would give up all sournesses.

By Linda Haviland Conte

35 pages, side-stapled

ISBN: 0972246011X, $8.00

Ibbetson Street Press, 2002

25 School Street, Somerville, MA 02143

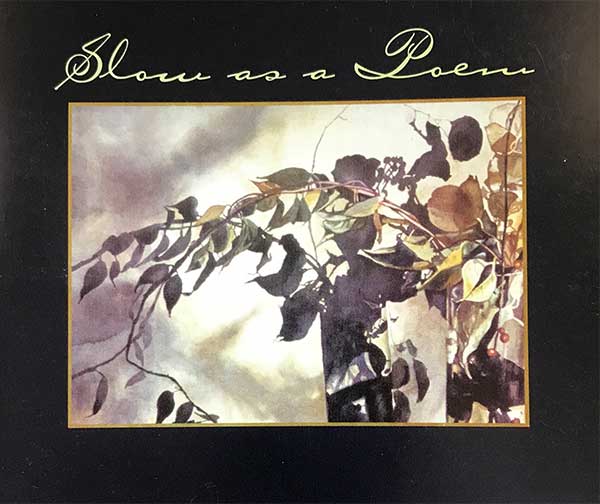

Life is not slow. If there is anything we come to discover as we live on, it is this. But sometimes, there’s a poet who comes along and grants us pause. Slow as a Poem is a lovely collection of moments bound together with the simple beauty of words.

I always used to shy away from poetry that relies so heavily on nature. But the imagery here goes beyond mere descriptions of beatific scenes. Conte mixes in aspects of meditation and uses nature as a teacher and also as a mirror. In these poems, nature reflects and reveals the qualities of both the poet and the people in her own life. She forms deep relationships with inanimate things–with the plants, the sea, the sky (“I am arranging animals out of clouds”), a boat, a book, and other imagined personalities. And many of the poems show how these things each contain an ability to heal, if one is willing to take the time.

The poem “Mom’s Time Out” is a lovely little poem about taking a well-deserved breather, with “symphonies of chirpers who don’t know / how to take turns, and I don’t teach them.” And “Immersion” left me wanting to dive right into the ocean myself. These words, these captured moments give permission to slow down and breathe. And slowing down refreshes and renews our spirits.

In the last few poems in her chap, Conte shares her hopes for people in general, and her own children in particular. “Child Home” projects into the next generation and muses about the quickness of life’s pace. One can either live life flying fast into the future quicker than it comes, or one can stop every once in awhile to reflect, as this poet does, on the simple things, all the colors in winter, the quiet moments that sometimes do float by, slow as a poem.

—Sara Medinger

The Boston Whaler rests in the slip ready

to perform the daily rounds: errands for Mom,

punctuated by wake-surfing adventures

and flirtations with the boys at the gas docks.

The hollow hull bobs on the river as I board,

making its friendly slurp and slap noises.

In the calm water there, a tiger-striped

perch darts back and forth, while a dull

rock bass puffs his big mouth and I wait.

A speedy motor-boat passes and

its wake rocks my boat and causes

it to press its bumpers into the dock.

In the distance a freighter plows

along the channel. A giant metal ox hoeing

a row in the St. Lawrence Seaway,

it dwarfs the triple-decker tour boat

passing on its port, full of sightseers.

The boat’s bench is warm from the sun and I bend

to tie my sneaker—an excuse for daydreaming

some more. A fresh breeze takes away the hot

motor oil scent, ruffles the surface of the water.

I am drawn to the chaotic rhythm of waves,

dazzled by the glory of shimmering light.

I am arranging animals out of clouds

when a crash of sandals against the gunwale

arouses me to the arrival of my big sister.

“Have you gotten the red water cans yet?

You are so slow!” Slow as a poem, I think

as she yanks the engine to a frenzied start.

He gamely tries to dandle my son,

his grandson, on his knee,

knowing I’d want that,

to see them together—

though next time we know

he won’t be strong enough

and I won’t bring my son.

He tries to tell me some story

from when he was young.

He knows I like those

and he produces a photo taken out

in preparation for our visit.

It must have been one of the first

cars his family ever owned,

a Model A Tudor Sedan, but

the people in the photo weren’t

anyone I’d have known.

A one-time Lieutenant Colonel

setting traps for Hitler’s forces

he quietly declares he’s tired,

and makes his way to bed while

Mom and I hover behind

lest he should fall.